We research, evaluate and select travel destinations based on a number of factors, including our writers’ experience, user reviews and more. We may earn a commission when you book or purchase through our links. See our editorial policy to learn more.

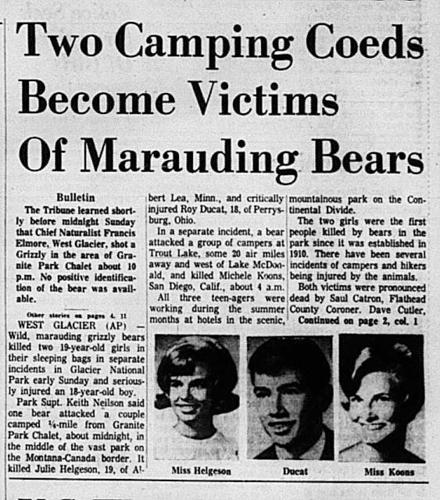

On August 13, 1967, just a few hours apart from each other, three campers were mauled by two different grizzly bears in Montana’s Glacier National Park, resulting in two fatalities. It was the first fatal bear attack in the park’s 57-year history and exposed massive problems in the ways humans were interacting with wildlife.

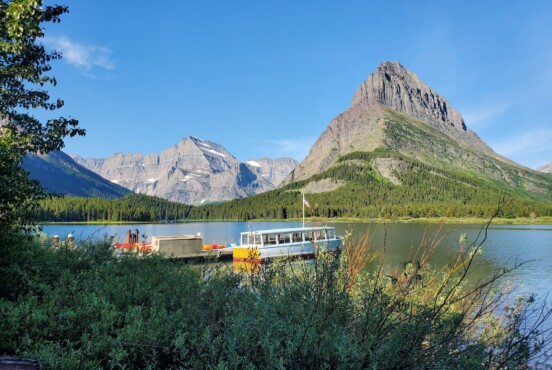

On August 12, 1967, 19-year-old Julie Helgeson went hiking with her friend Roy Ducat. Helgeson was a summer employee at Glacier, working at one of the lodges, and decided to use one of her days off to explore the park. After a long day of hiking, the two set up camp not far from the famous Granite Park Chalet.

In Night of the Grizzlies, a book that chronicled the fateful evening, author Jack Olsen wrote that in the middle of the night, some guests at the chalet awoke to the sounds of screaming coming from the woods. Down at the nearby campsite, Ducat and Helgeson were being attacked by a grizzly bear that walked into their camp while they were sleeping.

The First Attack

The bear gnawed on Ducat’s arm, mangling it badly before focusing its attention on Helgeson. It shook her so violently that she was torn out of her sleeping bag and then dragged away into the night. Ducat escaped to find help at the chalet.

A helicopter arrived with an armed ranger who would lead a search party to find Helgeson. As the party went out in search of the missing girl, the helicopter departed with Ducat, taking him to a hospital.

By the time they found Helgeson, she was almost dead after sustaining serious injuries and blood loss. According to Smithsonian Magazine, as she was being hauled towards the chalet, Helgeson kept repeating, “It hurts.” She died minutes before the helicopter returned for her.

But that wasn’t the only bear attack in the early hours of August 13th. Bert Gildart was a ranger at Glacier National Park that summer and told Territory Supply about the moment he learned of a second attack. Gildart was at the ranger station when the call came in.

“One of the rangers said, “Bert you gotta get up and go out to Trout Lake, there’s been a grizzly bear mauling.” I said, “No, that was at Granite Park Chalet.” Then he says, “Nope…there’s been another one.” I couldn’t believe it.”

Another Young Woman Is Attacked

Just 14 miles away from the first attack, another 19-year-old woman was fatally mauled. Michele Koons was also a summer employee in the park and she and a group of four friends decided to hike up to Trout Lake and stay overnight. At around 8 pm, a grizzly came into their camp and rummaged for food, prompting the group to grab what they could and make a new camp away from the bear.

But at some point between 4 and 4:30 am, the bear returned to the new campsite and attacked one of Koon’s friends, luckily only swiping at his sweatshirt, giving him time to flee. The campers began climbing into the trees to escape the bear, with Koons being the last one on the ground.

According to Outside, she wasn’t able to unzip herself from her sleeping bag before the bear slashed its way through and began mauling her arm. After a brief struggle, the bear dragged her off into the woods.

A Hunt for the Bears Begins

Despite some initial confusion about whether one bear had committed both attacks, it turned out that two different bears were involved in the maulings. Gildart was one of the rangers responsible for finding the bear that attacked Koons. When speaking to me, he recalled the moment he came face-to-face with the animal.

“A couple days after the attack, I was told to go try and find any and every bear I can until I was told to shoot it. That night I stayed in a cabin at the lake with another ranger, Leonard Landa. The next morning I got up early and stepped outside to take a leak, and I saw a bear standing about 100 feet away from me.”

“I hollered at Landa and said to bring the guns out. The noise of me calling him kinda startled the bear and it froze in place on the bank of the lake. The bear started raising his head, then lowered it, then raised it, then lowered it, like he was trying to figure out what I was. Then, all of a sudden the bear started moving toward me. I shot the bear and then Leonard shot it.”

After the bear was killed, the NPS flew a forensic expert from the FBI into the park to conduct an examination. As Gildart recalls, “He went over and cut open the stomach and this big ball of blonde hair comes sliding out.”

Humans Were Responsible for the Killings

Before the “Night of the Grizzlies,” National Parks looked much different from today.

Littering was more common and the pack-in pack-out policy wasn’t heavily enforced. Garbage sat openly at campsites, there were backcountry dumps where trash was piled up, and bears were even lured and fed to put on shows for tourists.

In some parks, like Yellowstone and Sequoia, bleachers were even constructed to let visitors watch the bears.

This created a vicious cycle known as habituation. When speaking of the bear he had to kill, Gildart said, “The bear was habituated to the area. In other words, it had encountered so many people that it had lost all fear of mankind and had no qualms about trying to come into the cabin for food.”

Because humans were so often around food sources, and in many cases were actually providing the food in the form of garbage, wildlife in the National Parks began having an unhealthy relationship with humans. They were losing their fear of people and some argue were equating them with food.

In fact, eating trash could have directly caused one of the 1967 deaths. After the forensic study was done on Gildart’s bear in the park, its head was sent down to Montana State University. According to Gildart, the university put the head in a box filled with beetles that ate away everything, leaving only the skull, which the university then studied.

“In the back molars,” Gildart says, “was embedded some glass. The bear had crunched on this glass, getting it stuck in its teeth, and the continued crunching caused the glass to actually become embedded between its molars.”

Lots of speculation has come from this discovery, with some wondering if the bear was in constant pain and therefore easily agitated, and others wondering if perhaps the bear wasn’t able to eat normally because of the injury, causing it to search for an easy meal due to starvation.

Regardless of whether it had any effect on that fateful night, the fact that glass was lodged in the bear’s teeth is proof that it was eating garbage left by humans.

That Night Led to Major Changes in the National Parks

As tragic as the night remains, it brought about massive changes in the National Parks, starting with Glacier. From the examinations and assessments that were conducted after the killings, it became clear that wildlands needed to remain wild and that feeding wildlife and letting them eat garbage brings them in closer contact with humans, and potentially causes them to equate people with food.

Gildart is thankful for the changes the parks have made, saying, “Back in 1967, they weren’t doing the things they should have been. There should have been better policing because the campgrounds back then were a mess. Instead of enforcing pack-in pack-out, they encouraged people to dump their trash in one of these backcountry sites, one of which was in Trout Lake, which is where that bear was.”

“But that’s something they started doing the very next year after the attacks. It was mandated that the backcountry areas of Glacier would need better management and better policing. The dump grounds were all cleared out, we thankfully don’t have those anymore.”

Closing trails with heavy bear activity also became a common practice to limit potentially fatal encounters, as did what Gildart calls “aversive conditioning,” which is where you use non-harmful practices to make bears afraid of a particular site to limit interactions with crowds.

These measures are more important now than ever as human-bear interactions are on the rise. According to Backpacker, thanks to better environmental policies, bear populations continue to rise after being almost hunted to extinction (in 1975, only 136 grizzly bears were left in Yellowstone).

On top of that, more people than ever are getting into outdoor adventure, both for the health benefits and due to the resurging interest in the outdoors that happened during the COVID pandemic. More people in the parks means there’s a greater chance someone will have a bear encounter — though it’s important to remember that a vast majority of bear encounters don’t result in any kind of physical altercation.

When in bear country, always remember that you are the guest in their home. Remember to leave no trace, pack-in and pack-out, don’t leave trash out in the open, and brush up on bear safety before venturing out.

More National Park Adventures

Get epic travel ideas delivered to your inbox with Weekend Wanderer, our newsletter inspiring thousands of readers every week.

Seen in: Glacier National Park, National Parks, News